The 8th dawned bright, clear and cold. The walk up to Nido de Condores is about 7-8 hours in total – at that altitude everything take a lot longer than would do in, for example, the Scottish hills. We left at 10.30am, and arrived at around 5pm. Sadly Paco had been unable to adjust to the altitude sufficiently quickly and was not allowed to come with us as we set off – he headed back to Mendoza to enjoy the sunshine, warmth and beer.

Evening sun in Nido, Aconcagua in background

Evening, looking over the rest of Nido

The walk was noticeably easier than the first porterage up to Nido, but I still arrived with a slight headache and nausea. In these situations, the nausea usually passes after 1-2 hours, and the best thing to do is to eat and drink as much as you can stomach.

The camp set-up

Once at Nido we set up several more tents so that in total we were 2 per tent. There is a total lack of running water at Nido so snow has to be taken from patches that lie round about and melted. Melting snow is a slow process, both in terms of speed at which it melts and quantity of snow required to produce enough water for 15 people (11 clients and 4 guides).

Sunset at Nido - 1

Food options at Nido were a lot more limited than at Plaza de Mulas – main meals were either rice or pasta based with sauce, followed by lots of high calorie snack options.

Before dinner the group had a discussion on the best way to attempt the summit. There are basically two ways to do the “normal” route – the first is 2 walk all the way from Nido to the summit and back again in a day; a total of about 17 hours and total height gain of around 1700m. That is a very big walk at any altitude, and there was some resistance against the idea. The second option was to spend the next day walking to Berlin, a cluster of 3 small huts and area flat enough to pitch tents, at about 5900m. After staying a night at Berlin we could attempt the summit.

Unfortunately Apu, our guide, was probably not as skilled at communicating as he should have been. There was quite a heated argument before it was decided that the group would have a rest day the next day before attempting the summit from Nido.

Sunset at Nido - 2

By sundown I had overcome my nausea and was feeling great. Even at Nido we were above the majority of the surrounding mountains and at the sky became dark there were stunning views in all direction. Above us the face of Aconcagua glowed red, whilst to away to the west jagged peaks faded into the distant blue. In the east snow capped mountains reflected pink and orange, and the sight was enough to lift everyone’s spirits.

Nightfall at Nido

The next morning I woke with my now almost constant head and neck ache, which I blamed on both carrying a fairly heavy rucksack the day before and the altitude. As usual, it improved fairly rapidly with ibuprofen and more sleep. The rest day was exactly that – eat, sleep, drink (lots!), plus some interminable discussions in Spanish as to the pros and cons of heading for the summit straight from Nido, rather than going to Berlin first. I was happy to do as Apu suggested – he was after all a professional mountain guide – but I could see that his manner left something to be desired. I put this down to his relative inexperience with large groups and age – he was only my age and dealing with experienced walkers twice his age.

We all turned in early for the 3am start for the summit.

We woke the next morning at 2.30am to the sound of howling gusts of wind. After fetching our water out of our sleeping bags (so it didn’t freeze overnight) we ate a heavy breakfast of stodgy cake before venturing outside, wrapped up in layers of thermals, fleeces and windproofs. Outside we were greeted by flurries of horizontal snow and a biting cold.

We set off only 15 minutes late and made very good time to Berlin at 5900m. Almost too good in fact – less than 2 hours instead of the normal 2-4 hours. I had taken a prophylactic ibuprofen already and, at our only rest stop on the way to Berlin, I took an anti-emetic to counter the nausea feelings that were creeping back in – although I wasn’t sure if they were altitude or breakfast related.

At Berlin we stopped for a quick bit of food. A thermometer on the nicest refugio (hut) read -17°C. At this temperature frostbite can become a real problem, and constant movement of fingers and toes is necessary to keep up a good blood flow and prevent it. I was feeling great by now, and was raring to go.

Berlin, taken during my descent

We set off again as a disjointed group. Henrik, Merced, Pepe and Vero turned back due to problems with tiredness, cold or severe headaches. The remaining 7 of us, with 3 guides, pressed on.

At about 6am light appeared on the horizon, and by 7am there was a magnificent sunrise with the shadow of Aconcagua clearly visible on the western horizon.

Aconcagua's shadow on the horizon

My earlier good feeling had evaporated and I was now starting to feel the familiar nausea feelings of previous ascensions.

Myself before Independencia, 7a.m.

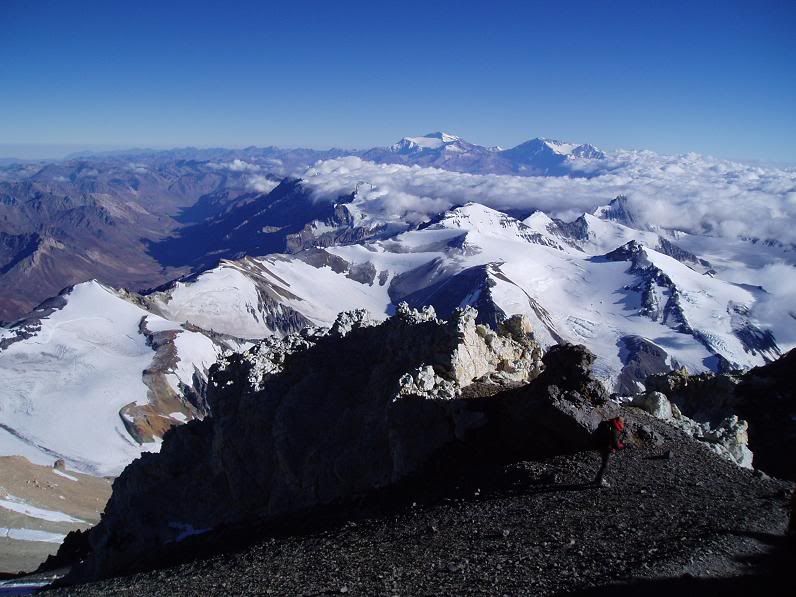

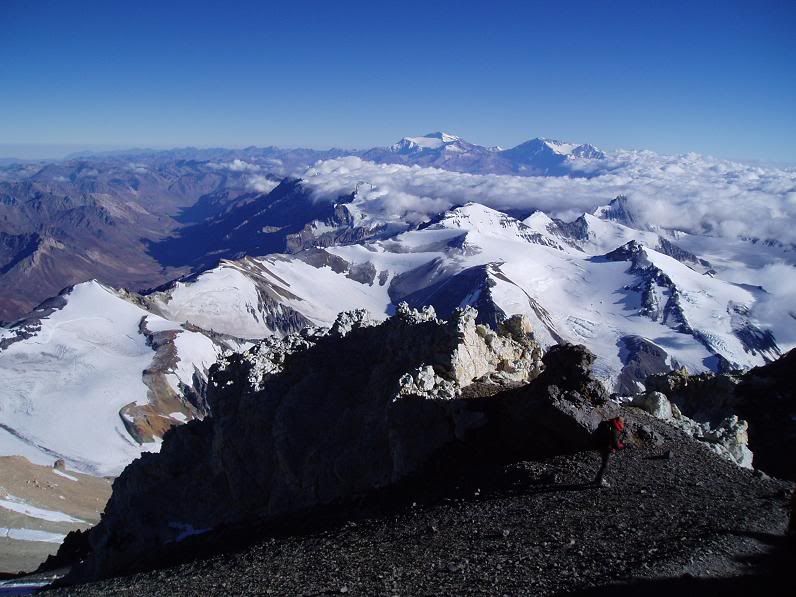

Views from below Independencia

At about 7.30am we reached the euphemistically named Refugio Independencia – an almost derelict tiny hut that has the privilege of being the highest refugio in the world. At 6500m it was still extremely cold, but out of the wind in the sun it was a little more comfortable than the previous hours. It was here that I decided to turn back – the nausea feelings were getting worse and every few steps I though I would throw up.

Going back - Independencia at 7.30am

I was left with strict instructions to back down the way I came (“Keep left! Do not turn off to the right! Keep left!”), and set off down the hill.

The rest of the group (3 guides plus the remaining 6) headed off to the bottom of the La Traversia, a 3 hour, uphill traverse across an exposed and windy scree slope. Beyond that was the dreaded Canaleta, a 2 hour climb up 260m of loose scree, followed by a relatively easy 1 hour walk to the top at 6962m. Relatively easy, note, but at almost 7000m you need to breathe with every single step, and it feels like there are lead weights attached to your feet.

During the descent - above Piedras Blancas and Berlin

I descended much quicker than I had climbed, but still had to stop every few steps to wait for waves of nausea to pass by. It was with some relief that I actually started throwing up when I got to 5700m. After that I felt a little better – both physically and mentally, as I think my body confirmed that I had made the right decision to come down.

I got back to camp at 10.30am or so, just as Anabolico, the guide who had gone down with the 4 others earlier, was setting off to help another member of our group who had fallen ill up the mountain. The Guardaparques had been in radio contact with our group and his help had been requested – little did I realise this help was for me! He climbed up to Independencia quickly and spent a fruitless 2 hours looking for a sick person.

Back at Nido, after about 6 hours sleep I was feeling much better and was able to eat and drink a little. The first of our party came back at 6.30pm – only 15 hours after setting out. The remaining 6 had all summited together at about 1.30pm. The last of our party got back in at 7.30pm, literally on their last legs.

The next day we headed back down to Plaza de Mulas where there was a celebratory lunch arranged for us. We sorted out our gear – the next day we were to walk the 40km out to the park entrance at Horcones, and so we were to send almost everything back by mule to make the journey easier.

After the dinner, back in Plaza de Mulas

The walk-out day started very cold and windy, but almost as soon as we began our descent from Plaza de Mulas it warmed up. After the long days at altitude it became easier to breathe again and vegetation reappeared at about 3500m. In the Andes vegetation ceases about 1500m lower than in the Himalayas, and biologists suspect that the effect of altitude on the body in the Andes is physiologically comparable to being 1500m higher in the Himalayas.

Back on Playa Ancha, Anconcagua in background

The end of the Inferior Horcones Glacier, a black tumbling mass of ice

We headed into La Confluencia briefly for lunch, greeted by the still crazy Matias, before covering the last 10km back to the park entrance in time for a transfer back to Mendoza.

As we walked out the park for the first time we could see all of the south face of Aconcagua, cloud free, rising 4km into the sky. It was as if she was saying her final farewell before we picked up our later transfer back to Mendoza.

Aconcagua's farewell

Finished at Horcones

And next? Well, I'm back in Mendoza enjoying some R&R. On Thursday I fly to Ushuaia in Tierra del Fuego, popularly know as the End of the Earth.