Road here is a loose term - mostly it is gravel tracks, or ripio as it is known locally. In Patagonia almost all roads have this same bone shaking ride - max speeds are 60km an hour for the most part. Places are being surfaced slowly, mainly to allow a smoother ride for the increasing tourist trade in the region.

We arrived in El Calafate early afternoon. The town, built almost entirely on tourism, sits on the edge of Lago Argentino, a vast lake fed by the Southern Patagonian icecap. Close by is the southern part of the Parque National Los Glaciares - a huge park preserving the icecap, it's sub alpine forests and tundra around the lakes that it feeds. The views from El Calafate across the lake are nice but the town felt like, and was, designed for middle class tourism that prices the average backpacker out of the market. I stayed in a new hostel overlooking the town and the lake - it had a lot going for it but lacked the atmosphere of the Antarctica Hostel in Ushuaia, my favourite stay so far.

Sunset from El Calafate hostel

On the bus I met up with 3 French travellers who had been on the Ushuaia, and who I had bumped into in Torres del Paine. We arranged car hire for the following day, to go and see the Perito Moreno glacier (the main attraction of the entire town) at sunrise. Perito Moreno glacier (there is also a town and National Park of the same name) is an advancing glacier that comes off the icecap and into a lake - in winter it can advance all the way across the lake and block it, only for the ice to spectacularly rupture during the summer months as it melts back.

Perito Moreno glacier

After the early, cold start, my hopes for a nap in the car were dashed by the ripio road, and we juddered our way to the glacier, the only benefit in my eyes being that we avoided paying the 30 peso (6 GBP) park entrance fee. The sunrise was spectacular but didn't touch the glacier - lots of deep pink and orange lit the hills behind us as the glacier continually calved small bergs into the lake. It was impressive, even after Antarctica. We left, pleased with ourselves, as the main tour buses started arriving with their payloads of snap-happy gringos and Argentines; our good moods almost evaporated when we had to pay to leave the park, the Guardaparques being more intelligent than we had given them credit for.

Sunrise at Perito Moreno

Back in El Calafate after lunch, and I got my ticket to El Chalten, 220km north in the same National Park, but sitting at the bottom of the incredible Fitzroy massif. I left the next morning, a little disillusioned by the way Calafate had turned out.

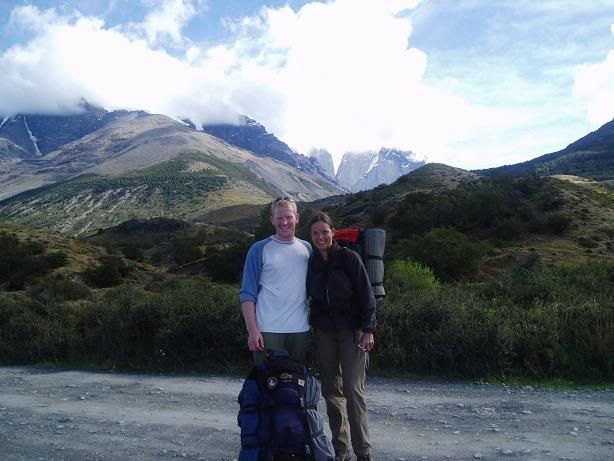

El Chalten is a town only 20 years old, built specifically for tourism. It has the feel of a real frontier town - 220km down a dirt track will often do that - but looks much older due to the constant sand-loaded wind. We arrived in driving horizontal rain, and I scurried as fast as my pack would allow to the hostel I had booked. I wrote off the afternoon's planned walk and explored the tiny town instead (pop. 400), getting provisions for my next couple of days instead.

The next morning dawned bright and clear, and there was a tangible air of excitement as people prepared to head up to the Fitzroy lookout, 12km away through virgin beech forest. Fitzroy was glowing orange as I departed, and it stayed in view most of the way there, gradually becoming a bright shining beacon in the surrounding country. The two most famous mountains here are Cerro Torre ("tower") and Cerro Fitzroy; Fitzroy is named after the Captain of The Beagle, whereas all the surrounding peaks are named after famous French aviators. I have yet to discover why.

Fitzroy

I was first to the lookout that morning and basked in the sun in a sheltered spot, admiring the view. Predictably (for those who know me) I woke up hour an hour later as more walkers arrived. I left, heading to Piedras Blancas, another glacier ending in a lake, with huge white boulders lying at the terminal moraine. Thoroughly pleased with the day's walk, I made my way back to the hostel with a few other young travellers and shared beer and dinner with them later.

Sunrise at Fitzroy at the hostel

The weather was not as kind the next day.... low cloud, wind and rain made for a pretty unappealling walk. After procrastinating for the morning, I had a long lunch then made a quick round trip to the Laguna Torres. The brief sunshine of early afternoon soon turned into heavy rain and I returned drenched after 19km and 3 and a half hours. Fortunately the hostel was equipped with a huge log burning stove, as almost all buildings are here, and I dried out pretty quickly.

The next morning I was heading up Ruta 40 to Perito Moreno (the town) - 530km on ripio road through highly recommended scenery. If before it was Wyoming, now it looked like Nevada - a very dry environment where the odd farm clung to life admist the dying scrub.

Ruta 40 going north

We only stopped twice in 12 hours, both times emerging into the hot, dry wind carrying inescapable dust that stuck to the skin and caked clothes. The scenery was excellent, but I was relieved to reach Perito Moreno and even happier to organise a trip back down the road to Cueva de los Manos with 3 Irish guys the next day.

On the road

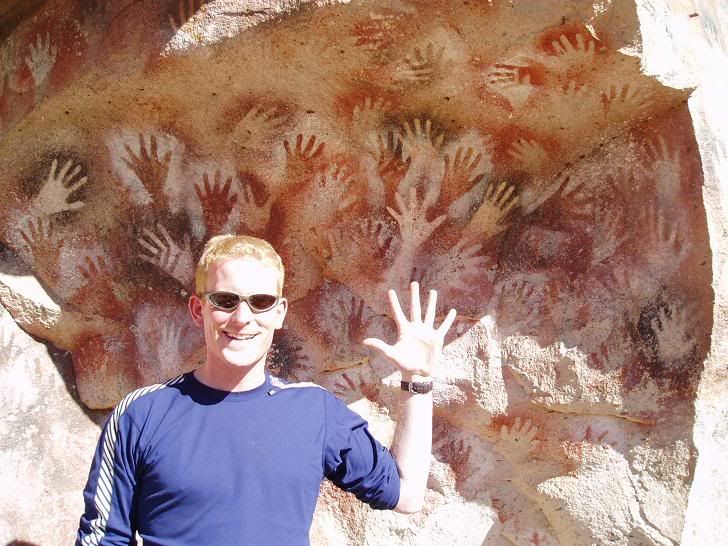

Cave of the Hands.... start counting!

Cueva de los Manos is a 13,000 year old collection of cave paintings - mostly hands but also guanacos and other animals. The hands are negative images, created by blowing a pigmented mixture chewed up in the mouth through a small bone and sprayed onto a hand pressed against the wall of the caves. Often hands were overlaid and in different colours - the effect is a bewildering kalaedoscope of colours that seems to reach out, in more ways than one, to the modern day tourist. There are 800 left hands and 31 right hands, plus a few guanaco, emu and puma prints. The origins if the paintings are still poorly understood - as usual there are a lot of theories and little in the way of proof.

I was really pleased to have made the effort to stay in Perito Moreno to go to the caves - it was well worth the extra effort. And in the process I had bumped back into Ray, from the Ushuaia, and we arranged to head to Coyhaique in Chile together to go to the Carretera Austral.

It had to be done!